China: coming out of the shadows

Growth of shadow banking is an integral part of the development of China’s financial system; all developed countries also have shadow banking sectors. That said, its expansion in China was also driven by banks' risk appetite to pursue high returns against a backdrop of slower economic growth, economic rebalancing and behind-the-curve regulation of the sector.

Structural changes in the economy are driving the appetite for risky assets

China’s shadow banking can be traced back to the 1970s, but it grew very slowly, until after the global financial crisis in 2008. Now the shadow banking boom in China has become a global concern.

The core story at the heart of the evolution of China’s shadow banking sector is the pursuit of higher returns by the financial sector – in performing its core function of capital allocation – via the allocation of funds into riskier assets in banks’ portfolios all the while set against a backdrop of slowing economic growth that was manifest in a declining return on capital (ROC). It is this process that generated such rapid growth in shadow banking.

Although shadow banking activities can be defined in various ways, in essence they share the quality of offering the opportunity of regulatory arbitrage – the institutions perform as banks, but their activities are not necessarily subject to normal bank regulation. In this sense, we can define shadow banking as the part of the financial sector that performs activities involved with regulatory arbitrage, no matter how the funds are raised and used.

Things you need to know about China’s shadow banking

Gauging the size of shadow banking

Our all-encompassing measure of China’s shadow banking estimates that its size has surged to RMB122.8trn in 2016 from RMB19.4trn in 2010. However, difficulties in measuring the size of the shadow banking sector do exist, with the lack of uniform definition of the sector and poor data availability being the two major obstacles.

Entering riskier waters and the two sides of shadow banking

While the shadow banking boom is a part of China’s financial liberalization – and an important funding source for the private sector – it has also increased systemic risks by lifting leverage and dressing-up bank’s asset quality.

The sector is something of a double-edged sword. It channeled money into local government financial vehicles (LGFVs) and those industries suffering from overcapacity, which are inefficient yet somehow able to afford the higher cost of financing due to soft budget constraints. On the other hand, it can also help facilitate financial liberalization by channeling funds towards the more efficient private sector and overseas investment.

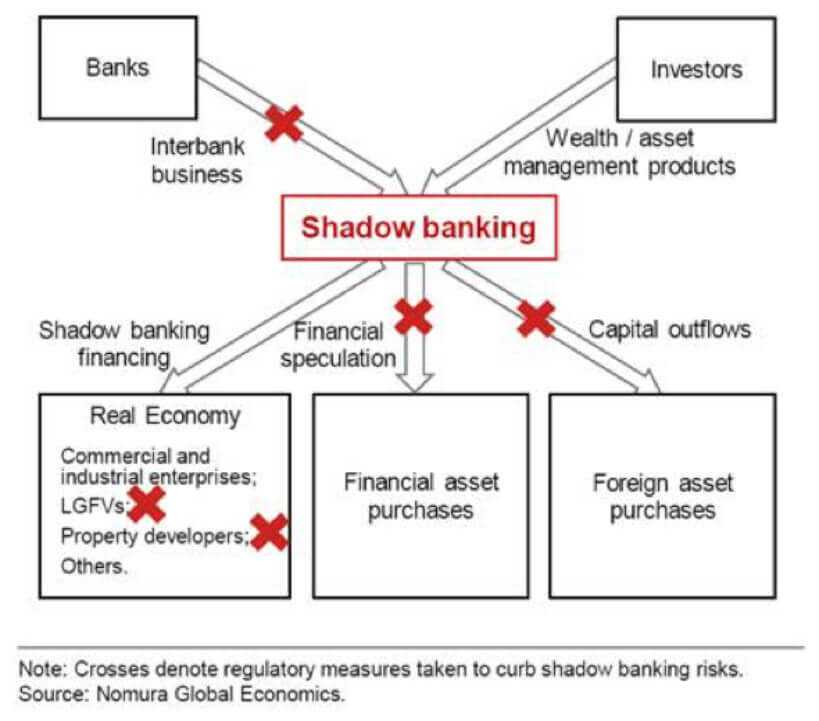

Financial deleveraging: moving risk-off

Financial deleveraging, which began in mid-2016 and targeted shadow banking activities, enforced higher costs for higher risk taking. The crackdown on shadow banking has been accompanied by capital controls. The risk reduction thus far has somewhat perversely manifested itself in a shift of fund flows towards state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and large companies, away from the private sector. Further deleveraging, however, will in our view lead to a risk differentiation in future, but deleveraging and capital controls are likely to continue and be in place for many years. Financial reforms, looking to replace indirect financing (by the banks) with direct financing (from the capital market), will increase transparency in the shadow banking sector and allow the capital market to price risk more accurately.

The China’s risk-off framework below highlights the deleveraging process aimed at reining in shadow banking activities and lowering systemic risks in the financial system.

The future of shadow banking

China’s capital market continues maturing, the key for regulators will be to minimize and control the risks that shadow banking poses. Ongoing and tighter regulation over time is likely to rein in the extreme pace of the sector’s early expansion and the positive opportunities that it does provide should be nurtured. As China’s capital markets deepen, the shadow banking sector should become more transparent and less risky.

The tightening of regulations on shadow banking is expected to continue, not necessarily being intensified but certainly in a more coordinated manner. Despite its long-term effect of reining in systemic risks, the negative impact on the economy in the medium term will begin to unfold.

Read the full report here for further insights into how China has been coming out of the shadows.

Contributor

Yang Zhao

Chief China Economist

Albert Leung

Asia Rates Strategist

Disclaimer

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.