Central Banks | 3 min read July 2020

Economics | 3 min read | August 2020

Deglobalization: The past and future

The tide of deglobalization is reshoring and gathering momentum, who is set to benefit?

Economics | 3 min read | August 2020

The tide of deglobalization is reshoring and gathering momentum, who is set to benefit?

The COVID19 pandemic has given deglobalization some momentum although it may alleviate some woes such as worsening inequality it could come at a cost of impairing productivity, raising prices, slowing the growth of emerging markets and triggering even worse effects. The ongoing global pandemic may speed up deglobalization, as nations and multinational corporations (MNCs) reassess risks and weigh resilience and national security more heavily than efficiency.

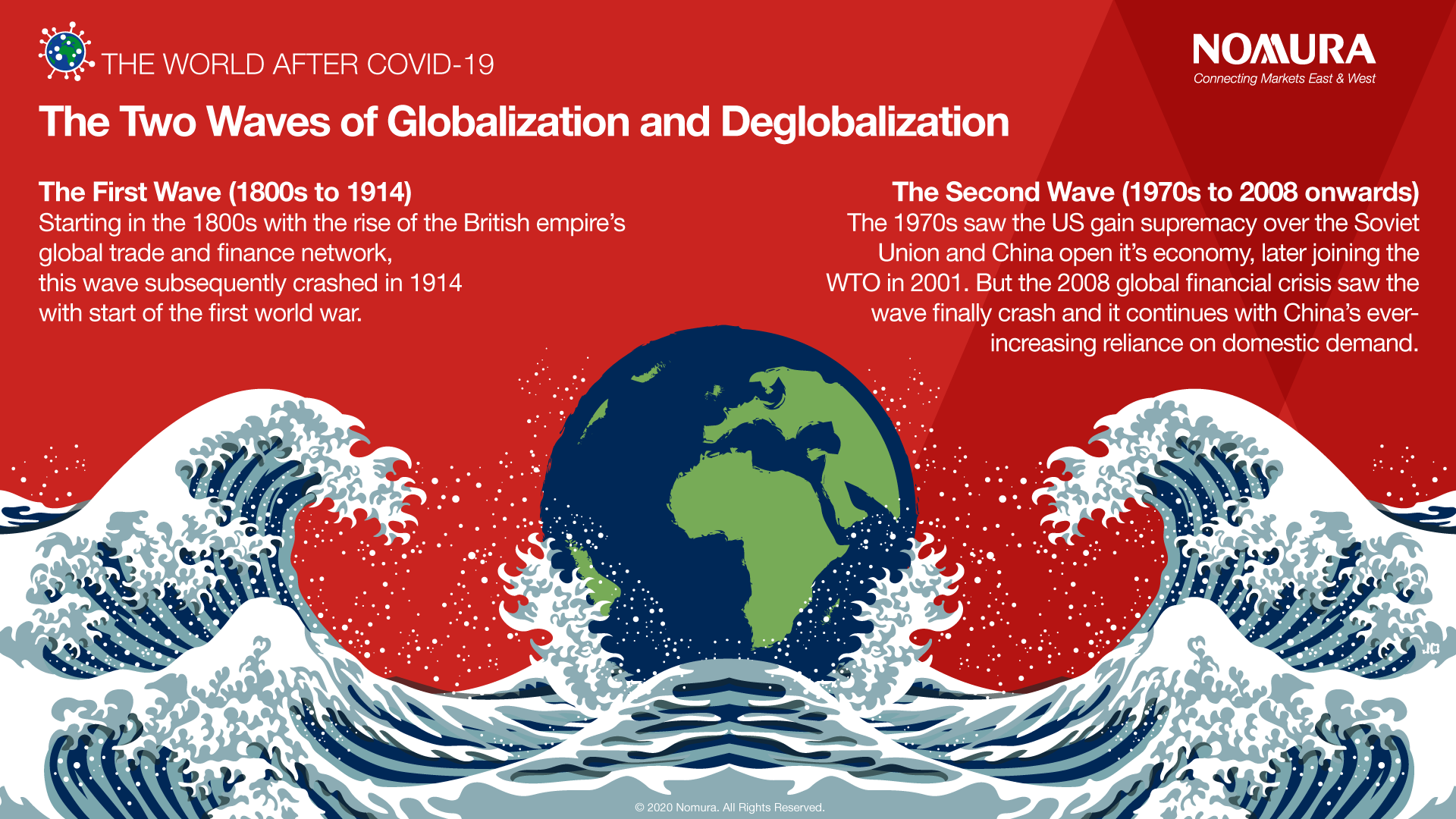

The first wave of globalization occurred in the 1800’s when the British Empire dominated global trade and finance. This globalization came to an abrupt end with the advent of WW1 in 1914. The second wave of globalization began in the 1970s, when the US gained supremacy over the Soviet Union and the socialist block gradually broke down. The pace of this second wave of globalization surged when China opened its economy at the end of the 1970s and later joined the WTO in 2001.

Most economies agree that globalization increases economic growth, raises living standards, lifts poor countries out of poverty and brings about net gains in society, but globalization also ambiguously creates winners and losers. Even among winners, the distribution of gains can be uneven across economies and social classes. Developed economies benefitted massively but the exodus of low-end labour-intensive industries in the manufacturing sector have widened the gap between Main Street and Wall Street, resulting in a strong backlash against globalization over the past two decades. The populism from the backlash has already significantly reshaped the political landscape of many developed countries.

One key feature of the second wave of globalization is that the mobility of capital was much higher than that of individuals. COVID-19 could exacerbate the gap of cross-border mobility between capital and labour. On one hand, social distancing rules may remain in place to some extent, as COVID-19 drags on, further limiting worker movements. On the other hand, a new round of quantitative easing aimed at migrating the effects of the pandemic has further reduced interest rates in developed economies, widening the interest rate differential between DM and EM countries. To chase higher returns, investors could deploy more capital to EM countries, with some capital in the form of financial flows and other capital in the form of foreign direct investment. Thus, even though COVID-19 may lead to deglobalization and reshoring to some extent, it may not be able to reduce inequality and bridge the gap between Main Street and Wall Street.

We now believe a protracted pandemic is likely. Countries may only reopen slowly, amid much stricter constraints on the flow of individuals rather than the flow of goods. If people refrain from travelling abroad, the adverse impact would likely be first seen on countries that are heavily reliant on the tourism industry, in our longer-term view, countries where the population growth has benefited from immigration face the risk of lower potential growth. If countries are compelled to limit immigration, they could go from having high sovereign bonds yields due to their high potential growth, to turning into low bond-yield countries, in an extreme example, like Japan. Thus, this potential structural change in demographics driven by the spread of COVID-19 could alter the global flow of capital.

For further insight on the world post Covid-19, read our full report here.

Chief China Economist

China economist

Asia Economist

FX Strategist, Economist

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.

Central Banks | 3 min read July 2020

Geopolitics | 4 min read August 2020