Japan in focus | 3 min read September 2024

Japan in focus | 3 min read | May 2025

The Japanese Economy Sheds its Skin

The year 2025 could be a turning point for long-term economic change.

Japan in focus | 3 min read | May 2025

The year 2025 could be a turning point for long-term economic change.

In the Chinese zodiac, 2025 is the year of the snake. Japan’s Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has said, “The year of the snake is a year for rebirth and evolution, because snakes repeatedly shed their skin as they grow larger.”

We believe the economic transformation of Japan is likely to take shape in 2025. In this period of global uncertainty, it might be time for longer-term investors to seriously consider Japanese equities as a useful diversified investment target.

At the macro level, we have observed the following transformations taking place in Japan:

We look at each of these transformations in more detail below.

This year will likely see the fourth year of price hikes, the third year of wage hikes, and the second year of interest rate hikes. If these hikes become entrenched, Japan’s economy will return to normality for the first time in around 30 years.

However, price hikes and wage hikes are not yet feeding off each other to a sufficient extent, which means Japan has not realized the virtuous cycle between wages and prices that the BOJ often references.

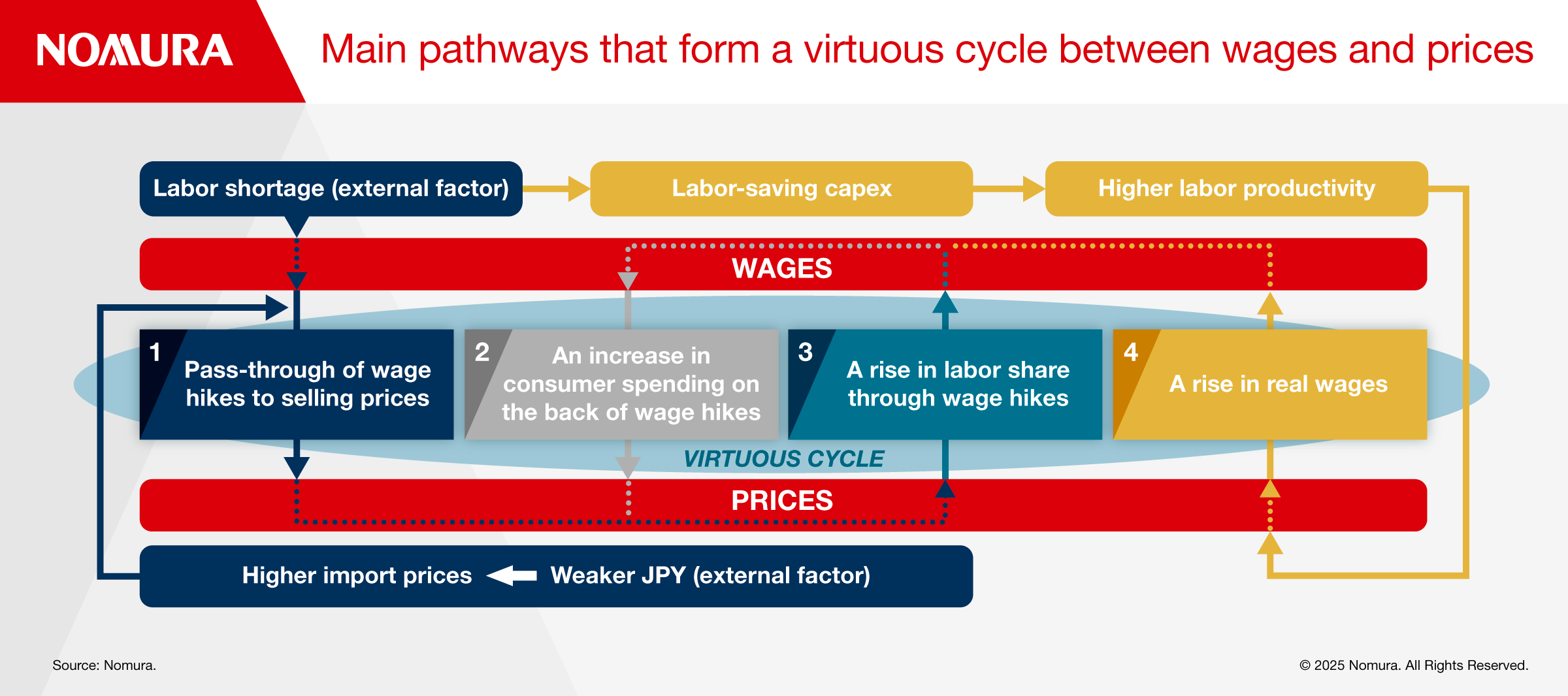

There are four pathways to achieving a virtuous cycle between wages and prices: (1) passing wage hikes along through price increases, (2) increasing consumer spending by increasing wages, (3) distributing income to workers through wage hikes, and (4) increasing real wages.

Japan is starting to see the first and third of these. Meanwhile, we expect pathways two and four to start to function in 2025. Pathway four, a growth in real wages, is a situation where wages are rising more rapidly than prices. But how can companies increase wages more rapidly than the prices for their products and services without sacrificing their own profits? The answer is by improving labor productivity.

Japanese companies are starting to invest in capex in a bid to make greater use of automation, digitalization, and laborsaving technologies. If this strategy improves labor productivity in 2025, there could be an increase in real wages.

In turn, we might expect an increase in consumer spending, which could lead to an increase in prices.

In a normal economy, where these three types of hikes are entrenched, inflation is likely to rise, which could lead to an economy that is increasingly “homegrown”. The main driver of the economy should shift from exports to domestic demand, and the main driver of inflation should shift from import prices to wage hikes.

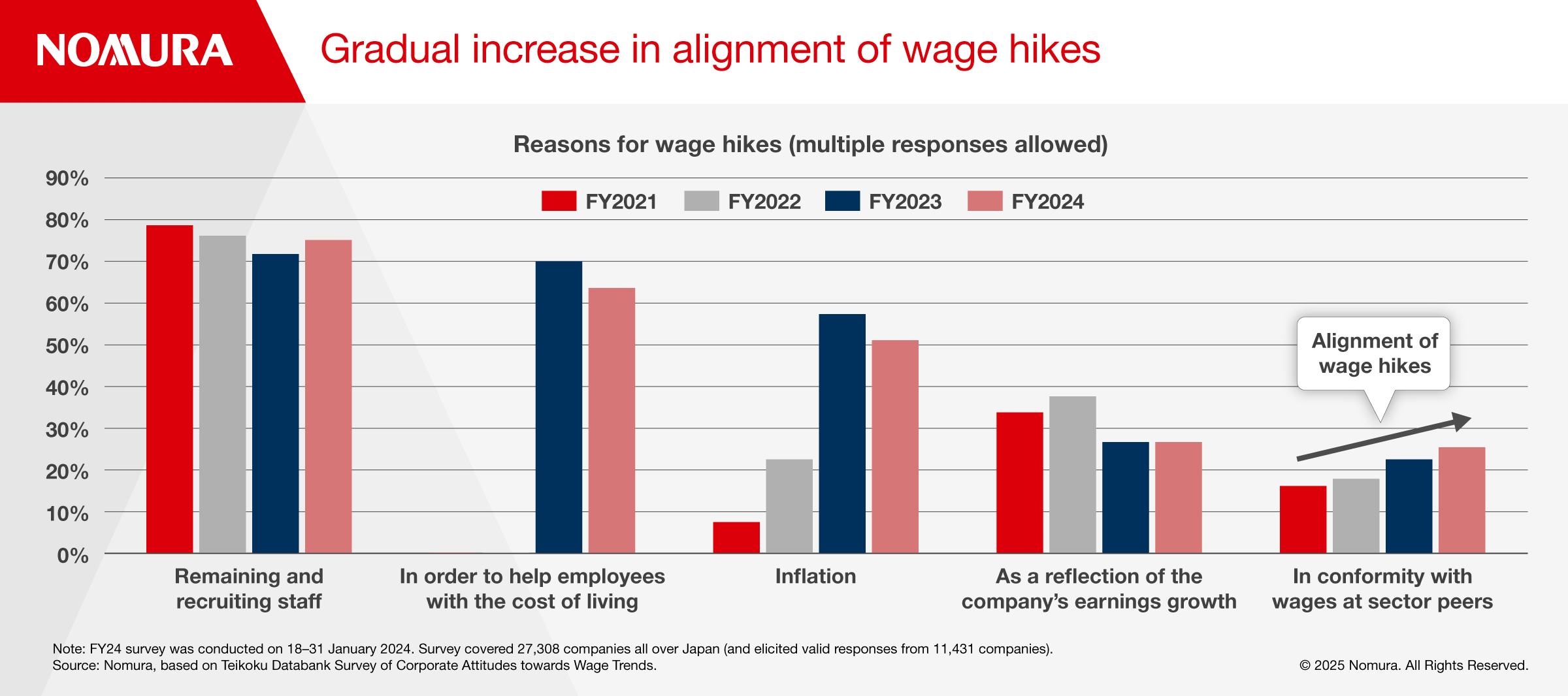

According to a Teikoku Databank survey, there has been an increase in companies that note the importance of wages at sector rivals as a reason for wage hikes, though the increase has been gradual.

This would mean that wage hikes are not only the result of external pressures in the form of labor shortages but are also turning into a spontaneous and aligned phenomenon.

Capex is a component of domestic demand, and exports are often cited as a factor behind changes in capex. Capex tends to rise (or fall) when exports are rising (or falling). In that sense, it can also be seen as a kind of derivative of exports.

According to a Teikoku Databank survey of companies planning capex, the second most popular item for capital investment, since FY2022, has shifted from “maintain or repair existing equipment” to “invest in digital technology”.

Companies’ perception of a shortage of facilities or equipment has not necessarily increased over the same period, which suggests they want to invest in digital technology for other reasons such as labor-saving initiatives in response to labor shortages, evidence of which can be seen in the clear upward trend in software investment that began around 2021.

To date, there has been a tendency to assume that BOJ monetary policy would move in line with that of other major central banks, so when the Fed was cutting rates, the BOJ would also cut rates (or, at least not hike rates), as Japan’s economy and prices are centered on exports.

However, if Japan’s economy became more homegrown, this would naturally cause a home bias in monetary policy.

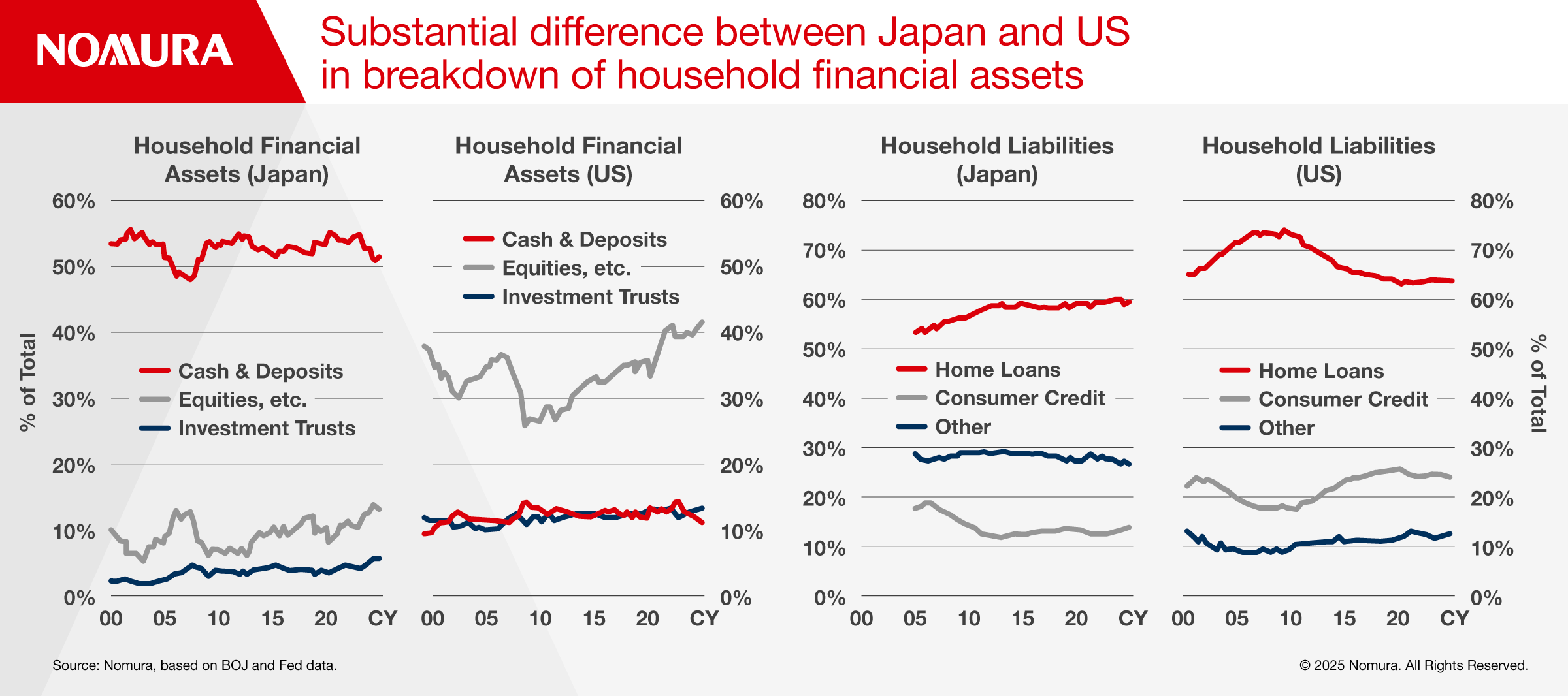

In January 2013, the BOJ positioned 2% inflation as its price stability target, yet Japan still struggled to escape deflation, and the purchasing power of cash and deposits did not decline. In this context, it made sense for Japanese households to favor cash and deposits, which account for around 50% of financial assets, well above the equivalent figure of 10% in the US.

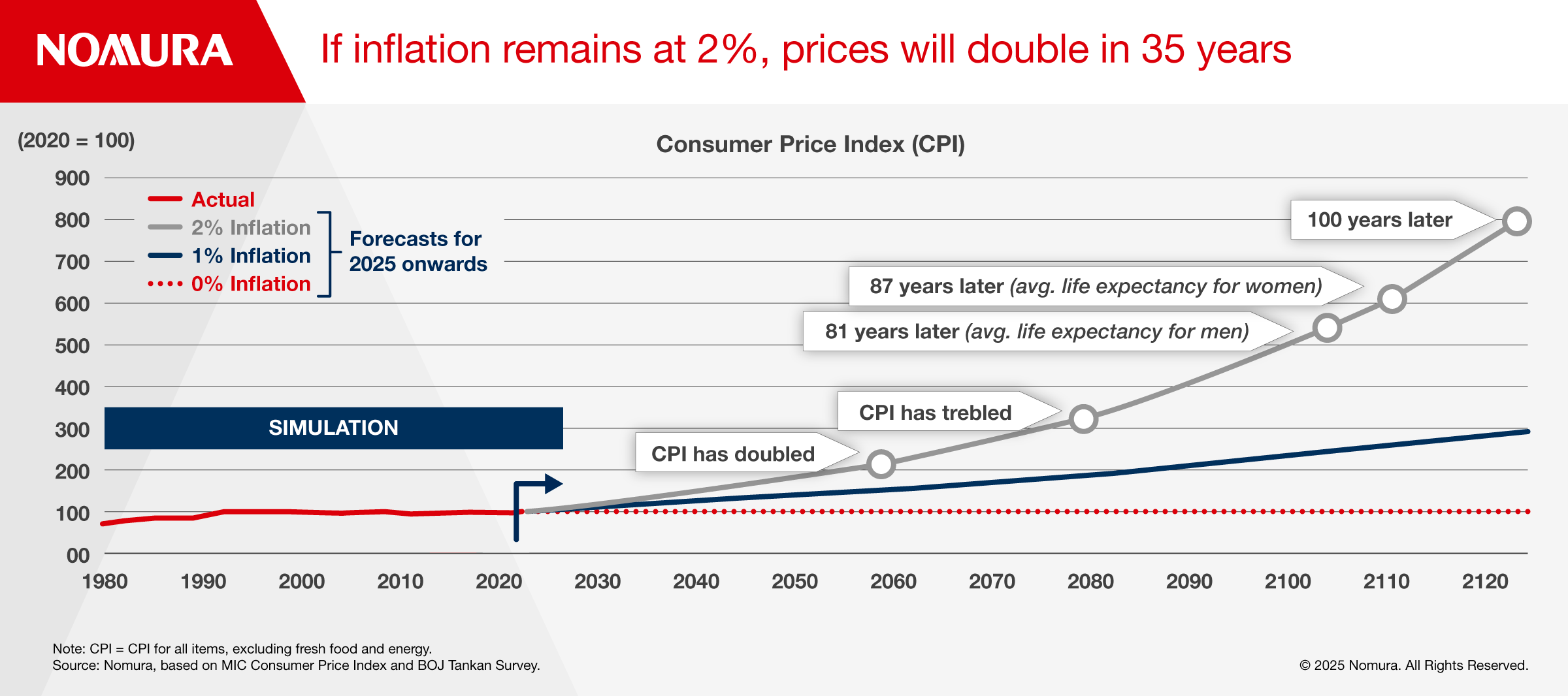

It’s too early to say for certain, but with wage hikes becoming increasingly aligned, inflation of around 2% might become the new norm. In this situation, a decline over time in the real value of cash—which doesn’t bear interest—and deposits would likely become the norm for Japan’s economy from 2025 onwards.

If inflation were to stay at 2%, prices would double after 35 years, triple after 55 years and climb 5x after 81 years (the average life expectancy for men). In other words, the real value (purchasing power) of cash would fall to half of its current level after 35 years, one-third after 55 years, and one-fifth after 81 years.

If the erosion of the real value of savings becomes entrenched, we expect to see three major trends:

First, a shift from savings to risk assets. This would mean a diversification into various types of risk assets that are well placed to withstand inflation such as equities and real estate.

Second, a shift from savings to consumption. In a world where inflation and low interest rates coexist, consumption could become more rational than holding cash and deposits (i.e. putting off consumption), the real value of which declines over time.

Third, a shift from savings to capex. Inflation corresponds to a rise in the value of goods and services produced by companies so investing in assets that produce goods or services for which the value will increase (i.e. carrying out capex) makes more sense under inflationary conditions.

If these three trends funnel the vast amounts of cash and deposits held by Japanese households and companies into investments and expenditure (consumption, capex), this could open up a pathway for economic growth as Japan’s population declines.

Chief Economist, Japan

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.

Japan in focus | 3 min read September 2024

Japan in focus | 3 min read April 2024

Japan in focus | 3 min read February 2024