Asia Economic Monthly: Food inflation risks are on the rise

Fiscal policy will be the first line of defense against rising food prices in Asia

- Though food prices have so far been tame, there is no room for complacency.

- El Niño conditions are expected to strengthen through the year.

- That could impact food crop production across Asia and lead to price increases.

Government intervention via fiscal policy is expected to be the first line of defense against rising food prices in Asia as the bar will be high for Asian central banks to raise interest rates due to negative economic growth effects and limited second-round inflation spillovers.

Food price inflation has been modest in Asia so far, though India is an exception. According to July data, food price inflation in India accelerated to above 10% y-o-y, up from 4.5% in June, largely amplified by volatile vegetable prices. Meanwhile, food price inflation remained in check elsewhere in Asia despite floods, typhoons, and drought.

Although food prices have so far been tame, there is no room for complacency. The conditions for El Niño, a natural climate phenomenon that results in less rainfall and limits agricultural production, are expected to strengthen through the year. That could affect rice crops in India and Thailand (the largest exporters of rice globally), wheat output in India, and palm oil production in Indonesia and Malaysia.

As rice is a staple food in Asia, a sharp rise in rice prices would have a much larger impact on consumers in this region. Singapore and Hong Kong rely on imports for 100% of rice consumption, while Malaysia and the Philippines import 42.7% and 24.2% of their rice consumption respectively. Within the region, the Philippines appears most vulnerable to higher food prices due to the 34.8% share of food in its CPI basket and net food imports comprising over 2% of its GDP. Meanwhile, India’s ban on exports of non-basmati white rice has pushed rice prices up for Vietnam and Thailand.

Upcoming elections in India and Indonesia could also indicate that protectionist policies are coming lest rising food prices exacerbate income inequality and result in voter discontent.

First line of defense: fiscal policy

Due to various government interventions in Asia, the rise in global food prices passes through to local food price inflation with an average lag of six months. This means that the current rise in global food prices, should it sustain, would be reflected in this region only towards the end of 2023 or early 2024, according to Nomura analysis.

Governments are expected to soften the food price impact via measures such as price controls, food subsidies, and crackdowns on hoarding. The authorities must keep in mind that some of these measures could in turn exacerbate global food price pressures.

Higher food price inflation is bad news for growth, both in the short term by weakening consumption demand and in the medium term via delayed policy easing. If food prices were to remain elevated, fiscal deficits in emerging markets may inch higher as governments spend more to support low-income households and current account balances take a hit due to import and/or export restrictions. We expect India’s twin deficits, especially fiscal finances, and the Philippines’ current account deficit to worsen.

Typically, higher food prices can result in second-round effects as a spike in inflation expectations prompts workers to negotiate for higher wages. However, in the wake of market uncertainty and weaker consumer demand, companies have limited pricing power which could lead to a squeeze on their profit margins. Weak bargaining power of workers and pressure on firms’ profits mean that a wage price spiral is unlikely.

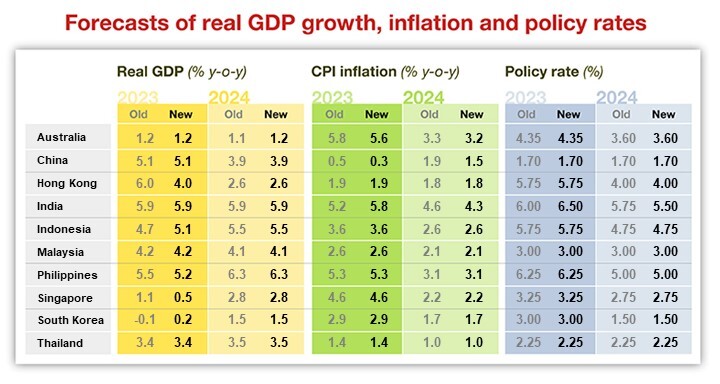

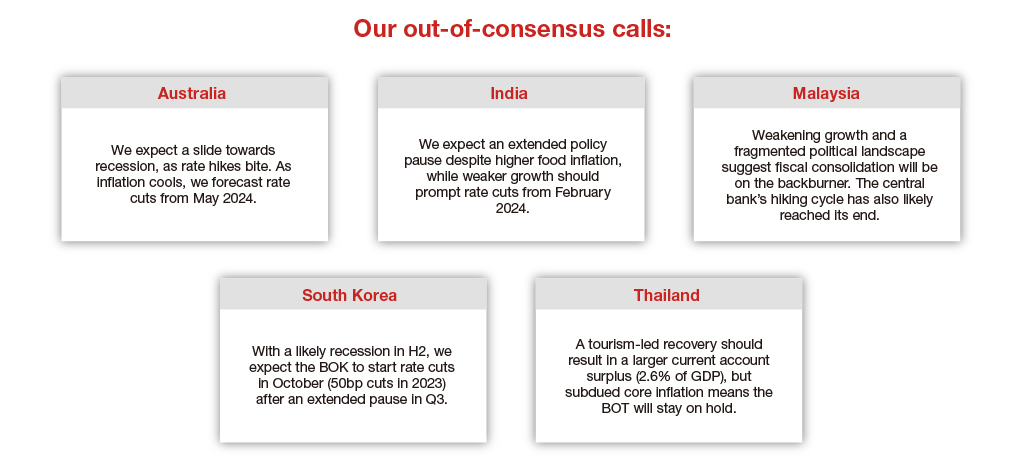

In the absence of these second-round effects, we expect Asian central banks to stay on hold for a prolonged period of time. In Nomura’s base case scenario, rate cuts could begin in Korea (October 2023), India (February 2024), and Indonesia and the Philippines (both March 2024). These rate cuts could be further pushed out in the case of a more sustained food-driven inflation surge.

For more on our 2023 growth projections, read our full report.

Contributor

Sonal Varma

Chief Economist, India and Asia ex-Japan

Si Ying Toh

Economist, Asia ex-Japan

Disclaimer

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.